Aorangi Mount Cook looms large in the 1898 Pictorials,

appearing both in the massive 5/- design and also in the diminutive ½d value. Certainly

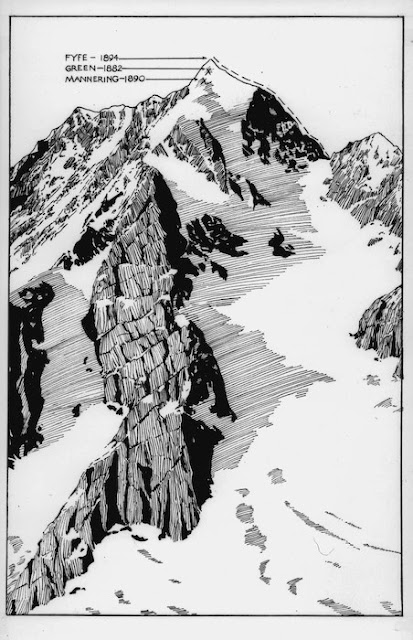

Mt Cook was topical, with major climbing expeditions in:

- 1882 (Irishman the Reverend Green and two Swiss climbers Kaufmann and Boss)

- 1890 (New Zealanders Mannering and Dixon)

- 1894 (New Zealanders Fyfe, Clarke and Graham).

|

1894: Highest points reached by the three climbing expeditions up until 1894. McLintock, Alexander Hare, 1903-1968. McLintock, Alexander Hare, 1903-1969: [Sketch showing details of earliest ascents of Mount Cook, 1882-1894]. McLintock, Alexander Hare, 1903-1968: [Making New Zealand ; originals for illustrations / A H McLintock and Paul Pascoe]. - [1939?]. Ref: A-258-023. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/23140773 (with cropping) |

The first two attempts were made from Linda Glacier to the north north east of the summit, but it was the third expedition, coming up Hooker Glacier then west then south along North Ridge, that was first to reach the summit of Aorangi Mount Cook. Accordingly it makes sense that the viewpoints for both stamp designs are from the Hooker Valley.

Meanwhile, it is the first expedition that is best documented via Green's engaging writing and especially his charming water-colours (see below). Accordingly, here we relay the travails and triumphs of that first expedition, as told by Green.

|

2 March 1882: The Worst Bit On Mt Cook Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. [Green, William Spotswood] 1847-1919: The worst bit on Mt Cook [1882]. Ref: A-263-010. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/23021971 (with cropping) |

|

Terms

arête: A thin,

jagged ridge that separates – or once separated – two adjacent glaciers

bergschrund: a

crevasse, or crack, that forms at the head of a glacier, where the lower, moving

ice separates from the stationary ice above

cornice: a

buildup of snow that overhangs the edge of a mountain, ridge, or gully.

Cornices can form on the leeward side of mountains, where wind deposits snow on

the downwind side of an obstacle. The summit of Aorangi Mount Cook is atop a cornice.

couloir: a narrow

gully with a steep gradient in mountainous terrain

serac: a

pinnacle, sharp ridge, or block of ice among the crevasses of a glacier,

oftentimes as large as a house

|

|

Unknown date but by 1882: Photo of William Spotswood Green Guy, Francis, 1820-1882. Guy, Francis, 1820-1882: Portrait of William Spotswood Green. Haast family: Collection. Ref: PA2-0790. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/22717046 (with cropping) |

Green published three articles in the Alpine

Journal of London (see their elegant site; where the material is also scanned and published by Google and HathiTrust). Green also compiled and preserved his personal collection of water-colours, which is now held by

the Alexander Turnbull Library. In the following, we interleave both these sources, where this effort is simplified given that copyright

has expired long ago. Modern

topographic maps are also provided for context.

At the time, Green characterized his expedition as a

successful ascent, albeit with a caveat: “… and surmounting the cornice without

any difficulty at 6 P.M., stepped on to the topmost crest of Ao-Rangi … The

cornice rose in a gentle incline to our right, so we advanced along it, keeping

a good hold with our axes, as the wind blew fiercely from the N.W. … My men now

urged that, as we were fairly on the summit of the peak, we should lose no more

time, but commence the descent; however, I wished to satisfy myself about a

break which I saw ahead of us in the cornice, and finding on examination that

it presented no difficulty whatever, but that it would have taken some minutes

to reach the slope beyond, I said I was satisfied, so … making a rapid sketch,

we commenced our descent at 6.20. … The highest point of the ice-cap was about

30 ft. higher than where we turned, and my only reasons for not going on to it

were that there was no view; there was no difficulty in reaching it; the twenty

minutes we saved was an important addition to the hour's daylight which still

remained for us to find a place of safety for the night”.

|

William Spotswood

Green (1847–1919) was variously a reverend, an

explorer and a marine scientist.

Green was born in

Cork, as the eldest and only son of six children of Charles Green, Justice of

the Peace and a merchant in the southern coastal town of Youghal. Despite having

an overriding interest in the sea, at Trinity College Dublin, Green took courses

in experimental physics, logic, mathematics, and physics and, after graduating

in 1871, took holy orders. Green was ordained deacon in the Church of

Ireland (1872) and priest (1873), and was appointed curate of Kenmare in 1874.

He moved to Carigaline in 1877, where he became rector in 1880. Both are southerly coastal towns.

Green married Belinda Beatty Butler in 1875. Like his parents before him, William and Belinda Green

had one son and five daughters too.

Green was able to

juggle his pastoral duties with adventurous trips around the world: the Orinoco

delta in Venezuela, the Swiss Alps, Aorangi Mount Cook, the Canadian Rocky

Mountains and the Selkirk glaciers; and afterwards Rockall Island (the last

three being in Canada). The Aorangi Mount Cook expedition was supported by the

Royal Irish Academy and Green authored a scientific account published in its

Transactions, then wrote a popular book, The High Alps of New Zealand

(1883), and presented a paper to the Royal Geographical Society (1884), which

elected him to fellowship in 1886.

From the mid-1880s

onwards, Green was increasingly able to spend time on his marine science passion,

and he retired from pastoral duties in 1890. At the same time, he was appointed

as one of the three inspectors of Irish fisheries, and he spent his subsequent

years towards Ireland’s fisheries where he “exerted a profound influence on the[ir]

development”.

Green led a

vigorous life as sailor and mountaineer, was noted for his sense of humour, and

excelled in personal relations with fishermen. This latter attribute was

invaluable as a source of insights about the industry. As we shall see, he was an

accomplished writer and watercolourist.

|

|

1882: Photo of the trio of William Spotswood Green (seated), Ulrich Kaufmann and Emil Boss (unclear if before or after their ascent). Edmund Wheeler & Son (Firm). Photograph of Rev W S Green with his guides Emil Boss and Ulrich Kaufmann. Original photographic prints and postcards from the file print collection, Box 17. Ref: PAColl-7489-08. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/23108344 (with cropping) |

Green’s trip to the Swiss Alps provided him with contacts in

the mountain village of Grindelwald. Two Swiss natives joined him on his New Zealand expedition: the indefatigable Ulrich

Kaufmann, who had a long and proud mountaineering record both before and

after the New Zealand expedition, and Emil Boss,

described as an hotelier from

the Grindelwald area, who continued with Kaufmann on a subsequent,

generally-successful expedition in the Himalayas.

|

Map Of the Southern Alps, by Julian Haast, annotated with Green's reported route (blue line). However, his map annotation shows that his rail route to Albury entirely followed the River Opihi but Albury (the red dot) is connected by rail along the more southerly Tengawai River then road (red line). |

The Alpine Journal, August 1882.

A Journey in to the Glacier Regions of New Zealand, with an Ascent

of Mount Cook. By the Rev. W. S. Green.*

Part

I or Part I

*The portion of Mr. Green's

narrative published in the present number was read before the Royal Irish

Academy on June 26 [Ed: 1882]. In following numbers Mr. Green will give a

detailed account of his attacks on and successful ascent of Mount Cook, the

highest summit of the Southern Alps.

The whole of New Zealand consists of a line of upheaved

stratified rocks, modified in the northern portion by recent volcanic activity,

and in one or two other places showing traces of more ancient vulcanicity. The

axis of elevation runs from S.W. to N.E., and is cut across into the North

Island, South Island, and Stewart's Island, by Cook's and Foveaux Straits. In

the South Island the mountains attain to their greatest elevation, and for over

100 miles the Southern Alps, as they were named by Captain Cook, raise their

peaks far above the snow line; in no place, for the whole of that distance,

descending to a col or pass free from eternal snow and ice.

Immense glaciers fill the valleys, and the remains of still

more gigantic glaciers are everywhere to be met with. This chain, with its

continuation north and south, seems to have been upheaved in Jurassic times,

and though it has experienced many vicissitudes of upheaval and depression, it

has never since, according to Professor Hutton, been submerged. These mountains

are, then, of vastly greater antiquity than their European rivals, and their

long exposure to the frosts and storms of ages is abundantly evidenced by the

heaps of loose splintered stones to which all except the higher peaks have been

reduced.

The mountains lie close to the west coast, their western

flanks possess a humid climate (the rain-fall at Hokitika being measured at 118

inches) and are clothed with forest and impenetrable scrub. The western

glaciers in some places extend to within 705 feet of the sea, and the rivers

are short and swift. This low descent of the glaciers, and the mean line of

perpetual snow being at about 5,000 feet compared with 8,000 in Switzerland,

where also no glacier descends to within 4,000 feet of the sea, is particularly

instructive when we consider that these Southern Alps are at about the same

distance from the Equator as the Pyrenees and the city of Florence. To the east

of the mountains the land drops suddenly to a level of about 2,000 feet above

the sea, and then, by gentle slopes and immense flat bare plains, sinks

gradually to the coast. The continuity of the plains is broken by ridges of low

rounded hills, which, on close examination, often prove to be old moraine

accumulations; while many of the plains are the basins of ancient lakes, the

old shores being very sharply defined. In the southern and northern portions

of the South Island this arrangement of mountain and plain is considerably

modified by the splitting up and bifurcation of the main axis of elevation, but

flat plains, extending to the very foot of the highest peaks of the main chain,

are most characteristic of New Zealand, and distinguish it from other mountainous

countries, where ranges of foot-hills have to be ascended and upland valleys

traversed before the higher ranges can be reached. In the province of

Canterbury, where the mountains attain their greatest height in Mount Cook, or

Ao-Rangi as it is called in the Maori tongue, these features are most

distinctly observable; the Canterbury plains, followed by the Mackenzie plains,

extending up to the very ice, and so flat that Dr. Haast said he would

undertake to drive a buggy the whole way from Christ Church to the foot of the

Tasman glacier. We tried it with an express waggon and three horses, and nearly

accomplished it. The country was level enough, but the boulders, as we drew

near to the glacier, proved a little too much for a wheeled vehicle, and the waggon

ended its days by being capsized in the Tasman river.

These New Zealand rivers have been a source of much

difficulty to colonial development. They are so swift and erratic in their

courses that fords are dangerous and bridges difficult to construct. Once the

rivers leave the mountains there is nothing to keep them to one channel, as the

plains, being composed of loose boulders and sand, are easily eaten away by the

swift streams swelled in summer by the melting snow. A river-bed is therefore a

broad sheet of gravel, through which a number of small streams wander, and

change day by day, what was a main channel one day being quite a secondary

stream in the lapse of a week or so. Much time was often spent in crossing one

river, with the delays of searching for fords, &c.; but now that railways

run north and south the problem has been solved on the most important route by

bridges, some nearly a mile in length.

In the province of Otago rich woods extend right across the

island to the east coast, giving place in many districts, however, to immense

plains covered with tussock-grass and Spaniard or sword-grass, except where the

farmer has come and adorned the landscape with waving fields of wheat. Farther

north the great snowy chain seems to form a complete barrier to the moisture

and vegetation of the west; the plains, hills, and valleys, are all bare, as if

shaven, the short grass being of the one uniform brownish yellow hue. Clumps of

flax (Phormium tenax) and isolated cabbage trees (Cordyline australis)

make the desolation appear more desolate. The rainfall is but 25 inches; the

air is clear, bright, and exhilarating; and when we do penetrate into the

furthest recesses of the mountains, to the very brink of the glaciers, we at

last come to a rank vegetation, brought into existence by the rains condensed

by the cold ice-peaks.

Acclimatisation has produced wonderful results in New

Zealand. On the great grassy plains where the moa once stalked majestically,

the skylark is now the commonest of birds, the sparrow threatens to become a

plague as the rabbit has done, and English weeds seem determined to establish

themselves and attain to a fertility unexampled at home. Clouds of thistle-down

fill the air, and sorrel usurps the ground prepared for oats and wheat. Among

other interesting points brought out by this invasion of the vegetable kingdom,

one at least is worthy of special notice, the failure of red clover, while

white clover thrives amazingly. In the neighbouring island of Tasmania red

clover grows well, and it is now believed that till the humble bee is

introduced to fertilise the flowers, red clover will not propagate itself in

New Zealand.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

On the 12th of last November [Ed: 1881] I [Ed: Green] sailed

from Plymouth for Melbourne in the Orient steamer 'Garonne,' having arranged

with Ulrich Kaufmann and Emil Boss, both of Grindelwaid [Ed: A Village in

central Switzerland], to follow me in the next ship [Ed: The Lusitania].

Unfortunately, small-pox broke out in my ship, and between a delay at the Cape,

and quarantine at Melbourne [Ed: This was well covered in the papers of the day,

and one passenger died, see for instance: 6

Jan, 7

Jan, 10

Jan, 11

Jan, 20

Jan, and 10

Feb], I was not able to reach New Zealand and join my men till February 5 [Ed:

Feb 5 was when New Zealand would have been first sighted

from the ss Te Anau. His port of arrival was Lyttelton

on Feb 9]. Immediately on landing I received a kind telegram from Dr.

Hector [Ed: Most likely influential New Zealand scientist and geologist James Hector, of Hector’s

dolphin fame, who lived in Wellington], and a letter from the Minister for

Railways, inclosing free passes on the New Zealand railways for myself and

guides during our stay in the colony [Ed: that ministry did not exist in New

Zealand until 1895; perhaps Green meant the Minister of Public Works,

Richard Oliver, who did hand out free

railway passes and who was in that role in 1880

and maintained some authority apparently beyond].

I lost no time in reaching Christ Church, where I spent an afternoon in Dr.

Haast's company, he being the great authority on the Southern Alps [Ed: Indeed,

the Alpine Journal article uses Julian Haast’s map of

the Southern Alps]; and next morning [Ed: 10 Feb] he started in the train for

the south. On arriving at Timaru we had a delay of three hours before the train

left by a branch line for Albury, and we occupied the time in purchasing

provisions for our mountain journey.

|

Zoom-Crop of the Map Of the Southern Alps, by Julian Haast, so as to highlight the annotated route of Green’s Mt Cook expedition. However, Green's map annotation (reproduced here as a blue line) shows that his rail route to Albury followed the River Opihi but Albury (red dot) is connected by rail along the more southerly Tengawai River and road (red line). Note that Hochstetter Glacier is named, but not Ball Glacier nor Linda Glacier, and not the Blue Lake(s) either |

As we were assured that we could get sheep right up to the snows of Mount Cook, we took with us but a small supply of meat in tins. Flour, meal, bread, and biscuits, formed the bulk of our stores. On reaching Albury by rail we hired a waggon and horses, and on the evening of the next day [Ed: Feb 11] we got our first view of the great snowy range. The contrast between the brown flattened downs over which we drove, and the purple ice-seamed peaks, was most striking. Next morning [Ed: Feb 12] we were up betimes, as we did not know how long our journey might be, and our driver was unacquainted with the country beyond this point. Our road soon lost itself in the rolling downs, so we walked on in advance, pioneering the way; and thus before midday we reached the last swell overlooking the Taman river.

|

12 February 1882: The Road To Mt Cook Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. [Green, William Spotswood] 1847-1919: The road to Mount Cook [1882]. Ref: A-263-009. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/23076006 (with cropping) |

We had now to descend about 200 feet, and again came upon

the track leading up the river-bed. This river-bed of the Tasman, over two

miles wide, is a broad sheet of coarse gravel, through which the river meanders

in countless channels, between which are often most dangerous quicksands. We drove

along over marshy flats on which numerous seagulls had their nests (one of

these young seagulls we afterwards met high up on the glacier, winging its

flight over the snowy range to the west coast), then across river channels and

over wide tracts of gravel. Right before us, rising abruptly from the river-bed

in the point where the valley forked, was the great mass of Mount Cook, its icy

peak glittering like a pinnacle of frosted silver against the deep blue sky. On

either side the mountains rose from the flat valley with the same abruptness,

and the terminal face of the Hooker and Tasman glaciers closed in the end of

the two branches into which the valley divided to the right and left of Mount

Cook. This flat river-bed, with the mountains rising from it abruptly, and from

margins as sharply defined as the shores of a lake, is so typical of all the

mountain valleys we saw, that we may ask-- 'What is the cause of a feature so

distinctive?' I believe the low level to which the glaciers descend, and the

consequent short incline of the rivers, is a sufficient cause. The terminal

face of the Tasman glacier is, according to Dr. Haast, only 2,456 feet above

the sea, while the means of four observations, taken on as many days by myself,

make it 100 feet lower, and its river descends to the sea level by a fairly

uniform incline of about 25 feet to the mile. If the river had a greater depth

to descend before reaching the level country or the sea level, it would erode a

deep ravine-shaped bed, like those so common in the European Alps. High up on

the mountain slopes on the side of the valley opposite to where we travelled

were the most remarkable series of terrace formations I ever saw, their level

being quite 500 or 600 feet above the present river, and their edges sharply

defined. Dr. Haast considers that they form part of the margin of an ancient

lake which was dammed up by a glacier crossing the valley lower down during the

last great glacier period.

Accepting in part this interpretation of the phenomena,

several interesting questions follow which we shall try to answer. What river

or rivers fed this lake? Was it the Tasman? The present source of the Tasman,

being about 200 feet lower than the terraces, would be below the level of the

ancient lake, so it could not have been the feeder, unless the lake existed in

an inter-glacier period, when the climate was milder, the ice-cap smaller than

at present, and the source of the Tasman higher up the valley. Supposing it was

not filled by the Tasman river, it seems to follow that at the time of the

existence of the lake the great trunk glacier formed by the junction of the

Hooker and Tasman must have filled up the centre of the valley, and, extending

far away down to beyond the terraces, formed the dam which banked up the

drainage of the hills above the terraces, and thus formed a lake similar to the

Merjelen-See, in Switzerland. At the same time the main drainage of the great

glacier passed along at a lower level, and issued from its ice-cave miles lower

down, as the stream of the great Aletsch does at the present day.

That the Tasman glacier has been down the present valley at

almost its present level, past the foot of the slopes on which the terraces occur,

is proved by the existence of several little mounds of old terminal moraine

which the river has failed to remove.

The heat as we journeyed up the river-bed was intense, dark

masses of rain-clouds blocked up the Hooker valley, while the Tasman remained

clear except for a passing shower. Along the course of the river small

whirlwinds followed each other at regular intervals, making themselves visible

by the cloud of minute sand which they whirled upwards to a height of from 50

to 100 feet. The track we followed was only made by bullock-waggons on their

yearly journey for the wool of the two sheep-stations near the head of the

valley; and the ruts were so deep that more than once our waggon was nearly

upset, and only by dint of slashing, hauling, and shoving, did we surmount some

of the difficulties.

Mt Cook Station to Birch Hill (click on the placemarks for further context)

At two o'clock, after fording a broad stream coming down

from the right, [Ed: Surely Jollie River] we arrived at Mount Cook station, and were hospitably received

by the proprietor, Mr. Burnett, and his good lady, who busied herself to provide

us with a meal, while Mr. Burnett found one of his shepherds to pilot us over

the Tasman. It was now three o'clock, and late to proceed, but my whole object

was to push ahead as fast as possible, so, in spite of the protestations of the

driver, we started, to get past what we expected would prove the greatest

difficulty of our journey. For a short distance the horses were able to gallop

over a grassy flat, the shepherd riding out in front, and every now and then

startling a small flock of Paradise ducks. On reaching the shingle of the river

we had to go on foot, only getting into the waggon when a channel of ice-cold

water deeper than usual had to be crossed.

|

12 February 1882: Tasman River Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: Tasman River, N. Zealand, [13 February 1882]. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: [Journey to New Zealand and the attempt on Mount Cook, November 1881 to March 1882, and] Dodging about Switzerland in 1879.. Ref: E-581-q-004. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/23241598 (with cropping) |

After fording about a dozen such streams we reached the

larger channels; here our pilot rode up and down, testing the fords, and when

the main channel was reached we got into the waggon. The water surged and

gurgled over the wheels, the horses got frightened, and just as we were in

mid-stream a splinter bar gave way and the horses became hopelessly mixed. The

wheels were settling down, the river welling into the bottom of our trap, and

the weight of baggage alone kept it from floating. There was no time to lose;

so, fastening a rope to the fore carriage, we ran along the pole, and from the

neck of the leader dropped into the river, where it was no more than knee deep,

and then, hauling on the rope, we got the waggon into shallow water, and

spliced the broken harness. Cold blasts now swept down from the glaciers, and

heavy masses of clouds obscured the sky. As our clothes were well wet, we

splashed recklessly along through the river channels, and at dusk reached the

grassy slopes of the farther shore [Ed: i.e., after crossing the Tasman River

east-to-west]. Here our pilot turned back, and we saw him galloping along the

shingle flats till he became a tiny black speck, and then vanished in the

gloom. We were now close to Birch Hill sheep-station, the last human habitation

toward the glacier world [Ed: Just south of Mt Cook Village on the western side

of the Tasman River]. Its wool-shed (a building of galvanised iron) afforded us

shelter; and, after a cup of good tea, administered to us by Mr. Southerland,

the young shepherd in charge, and a change of clothes, we slept soundly on the

wool bales, only occasionally aroused by the growling of the thunder, and the

rattle of heavy rain on the iron roof.

|

12 February 1882: Birch Hill Sheep Station Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. [Green, William Spotswood] 1847-1919: Birch Hill sheep station [1882]. Ref: A-263-012. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/23067926 (with cropping) |

Birch Hill Sheep Station to First Camp [Ed: The location of the first camp is reported as two miles past the southern tip of the the Kirkirikatata Mt Cook Range. From Green's various water-colours, we further infer that its location is on flattish land lying to the south-west of a stream winding its way from the range to the Tasman River.]

Next day, February 13, we packed our horses, and, assisted

by Mr. Southerland as guide, and two young gentlemen who had ridden up from

Timaru to see the glaciers, we got across the rapid torrent from the Hooker

glacier, and at 1 P.M. reached a patch of scrub about two miles from the face

of the Tasman glacier, and, unloading the horses, pitched camp [Ed: The first

camp]. We sent the horses back from here, with orders to return for us on March

7.

|

Circa 13 February 1882: Camp near the Tasman Glacier [Ed: perceiving this as showing a river rather than a glacier, then this presumably shows the lower (first) camp where the two tents are out-of-frame to the left. In the foreground we see 2 climbers besides the camp-fire and another climber standing; then the Tasman River; and beyond we there is a line of fire for sheep mustering on the hills on the left, then a gap (Gorilla Stream?) then a line of mountains behind on the right (a spur of the Burnett Mountain range?). Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. [Green, William Spotswood] 1847-1919: Our camp near the Tasman Glacier; mustering sheep on opposite hills [1882]. Ref: A-263-011. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/22752494 (with cropping) |

|

Circa 13 February 1882: Lower (First) Camp, Tasman Valley Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: Our lower camp, Tasman Valley. [February 1882]. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: [Journey to New Zealand and the attempt on Mount Cook, November 1881 to March 1882, and] Dodging about Switzerland in 1879.. Ref: E-581-q-007. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/22877283 (with cropping) |

February 14 was devoted to strengthening and doubling our tents against the weather, and throwing a bridge over the stream that flowed near our camp, and between us and the glacier.

|

14 February 1882: Bridge Near Our Camp Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: Bridge near our camp. [14 February 1882]. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: [Journey to New Zealand and the attempt on Mount Cook, November 1881 to March 1882, and] Dodging about Switzerland in 1879.. Ref: E-581-q-005. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/23217134 (with cropping) |

Early on the 15th we started from the camp, taking with us

some slight poles for observation on the motion of the glacier, my photographic

apparatus, our ice-axes, and provisions for the day. Crossing the bridge, an

hour's smart walking over grass-covered flats brought us to the terminal

moraine which rises up here in grassy knolls to a height of 200 feet, and

which, assuming a more recent appearance to the eastward, extends right across

the valley, a distance of about two miles in a straight line. Nowhere is ice

visible except near the farther shore where the river breaks forth. The

truncated form of this termination of the glacier shows, I think, that it

cannot be retreating very rapidly if it is retreating at all. As the absence of

any heaps of terminal moraine on the flat plains near to its face proves that

the river outlet must have changed many times along the present terminal face

to have so completely swept the valley of all outliers except one small heap

which has been protected by boulders of unusual dimensions. It may be

stationary, but from consideration of the appearance of the terminal face, and

from observations on the relations of the present lateral moraine to more

ancient ones to which I shall allude further on, I would conclude that the

glacier is at present advancing; or if it is not doing so at the present moment

it has done so since its last retreat, as there is good evidence to prove that

at a period not very remote the glacier was smaller than it now is.

We ascended the outer line of grass-covered moraine, and,

passing a little blue lake lying in a deep hollow in which we discovered

numerous small fish about four inches long, we ascended heaps of newer moraine

composed of immense loose angular boulders, and finding our progress over it

most fatiguing and slow, we turned off to the left in hopes that the lateral

moraine might prove more practicable, but finding it just as bad, and no level

ice being in sight, we descended to the hollow between the lateral moraine and

the mountain side. Here we were entangled in almost impenetrable scrub,

composed of Wild Irishman (Discaria toumatou), and sword-grass (Aciphylla

Colensoi), which cut us so cruelly that I quickly returned to the boulders,

and soon got far in advance of my companions, who tumbled about in the scrub.

Occasionally we got a more open bit for a change, but nowhere could we feel

ourselves safe from the chance of a broken leg or sprained ankle. After five

hours of this sort of thing we again surmounted the lateral moraine, and,

striking right across the glacier, in one hour reached the white ice. The cool

air of the ice was most refreshing after toiling over the heated boulders under

bright sunshine and sheltered from any wind. We walked briskly ahead until 2

o'clock, when we reached a point from which we had a splendid view of the great

cliffs of Mount Cook and the grand amphitheatre of peaks which swept round from

left to right. This view I consider quite equal, if not superior, to anything

in Switzerland, and the glacier beneath our feet had an area half again as

great as that of the great Aletsch, the largest glacier of the European Alps.

Tributary glaciers poured in with graceful curves from the mountain sides, and

long lines of moraine, from thirty distinct ice-streams which were in sight

from this point, brought their tale of boulders to add to the great rampart

which had given us such trouble to surmount. We scanned the great ice ridges of

Mount Cook with anxious eyes; all its approaches seemed most difficult; the

only point which was quite clear was that our present camp would not do, and

that, in spite of the roughness of the road, we must shift it up to where we

now were. As it was getting well on for 3 P.M. we decided we could at present

go no farther, so, selecting a mark on the hillsides, I set up a row of stakes

across the glacier [Ed: This would become the site of the fourth camp], and, having

secured a photograph, we started back for camp, which we reached at 8 P.M. On

our way we deposited our ice-axes, the stand of my camera, and some

photographic plates beneath a boulder, so as to have the less to carry on our

journey up the glacier.

View of Aorangi Mt Cook ("3" in large red placemark) from Tasman Glacier (star in small blue square)

February 15 was spent in selecting the necessaries for our

journey, and in cutting the flesh off the bones of the sheep, and making all

arrangements for an early start. Mr. Southerland who rode up to see how we got

on, kindly took a good-sized pack made up in our small tent, across the front

of his saddle, and, riding up to the moraine as far as his horse could go,

deposited it in some scrub, hung up a flag to mark the spot, and promised that

whenever he should see our fire burning again he would come up to see if we

wanted anything. At this lower camp the heat during the day was very great, the

temperature being often 82° in the shade; the air was clear, with barometer

ranging from 27.60 to 27.70.

A brisk breeze, occasionally blowing in sudden strong squalls

from S.W. or N.W., prevailed in the valley, while on the mountain ridges a

steady, fierce wind seemed to blow continuously from the W. The wood-hens or

wekas (Ocydromus australis) were a source of constant amusement; they

seemed to know no fear, and would come picking and examining every article in

our camp, and were always ready to bolt off with any small object left on the

ground. They cared little for the stones we threw at them, and all night they

kept up a constant whistling accompanied by a kind of grunting noise On the

stream hard by we had an inexhaustible supply of blue ducks (Hymenolaimus

malacorhynchus); there were never many to be seen at a time, but when we

shot three or four one day a couple of brace more would occupy the same part of

the stream next morning. They were not wild, so in order to save cartridges we

generally pelted stones to get them close together, and then tumbled two or

three in the one shot. Far more wild, though quite as numerous, were the

paradise ducks (Casarca variegata). These were splendid birds; in

habits, mode of flight, and note, resembling geese rather than ducks; and the

male, with his white head, kept such a good look-out that various stratagems

had to be adopted ere we secured one for the pot. There were a few mosquitos

and sandflies, but the large blowfly was the greatest source of annoyance. A

coat or a blanket could never be laid on the ground for half an hour with

impunity; even my mackintosh was considered a good receptacle for their eggs;

but we kept them from our cold mutton and ducks with a few yards of mosquito

net; and, after all, having your coat full of maggots does you no harm so long

as they do not, like the larval of moths, feed on the material.

[Ed: As well, Green dated a letter

on Feb 16 and it was published on Feb 23, so presumably someone such as Mr

Southland visited Green’s expedition at least once during this time]

We were astir at the dawn of February 16, and, as soon as we

had our packs ready and the tent secured against all wekas and other possible

invaders during our absences we started for the glacier. On reaching the little

red flag that marked our pack at the foot of the moraine we re-arranged our

loads, Kaufmann and Boss dividing all they had to carry into four loads, while

my swag consisted of my knapsack, a plaid, a mackintosh cape, a sack containing

my camera and plates, another sack full of cartridges, and the guns. It was

quite as much as I could manage over the rough ground. My men adopted the plan

of carrying one load each for an hour or so and then setting it down,

scrambling back again for the others, thus making the whole journey twice. In

this manner I arrived first at the camping-ground we had chosen near the shore

of a little blue lake, where the whole drainage of the valley that found its

way beneath the boulders bubbled forth to the surface; and I had the camp

pitched when my men arrived at dusk [Ed: Second camp].

First camp to Second camp [Ed: The location of the second camp is estimated assuming that Green's Blue Lake is the lake below a steep slope of the Kirkirikatata Mt Cook Range (which lake is also the largest of the modern-day Blue Lakes), and the camp's position relative to the lake is determined from Greens "Second Camp" water-colour.]

|

Circa 17 February 1882: Second Camp Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: 2nd camp [Tasman Valley. February 1882]. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: [Journey to New Zealand and the attempt on Mount Cook, November 1881 to March 1882, and] Dodging about Switzerland in 1879.. Ref: E-581-q-008. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/22875978 (with cropping) |

[Ed: Feb 17] The lake was embosomed in dense scrub which

here clothed the high moraine and the mountain sides. This scrub was composed

of dwarf pines, birch, or more correctly beech (Fagus), veronicas, sixty

species of which are indigenous to New Zealand; and shrubs of podocarpus,

coprosma, dracophyllum, &c. As we came along, we could not

resist eating the sweet red berries of Podocarpus nivalis, though at the

time we were not sure what ill effects might ensue. Of smaller plants, the fine

white Ranunculus Lyal ii was everywhere abundant; it goes by the name of

Mount Cook Lily among the colonists, and we found its large succulent leaves

most useful in our hats as a protection against the fierce rays of the mid-day

sun. A little white violet became common from this camp upwards, and ferns

nestled under the shade of every damp rock. Keas, or Mount Cook parrots, now

made their appearance and came screaming close to the tent. Kaufmann shot a

couple, and soon had them picked and in the soup-kettle, while Boss added a

brace of ducks to the larder. Parrot soup proved so good that from this day

forward we were never without some in the kettle. Since sheep were introduced

into New Zealand, these parrots have acquired a taste for kidney fat, and,

perching on the poor unresisting animals, eat through their flesh in order to

obtain this delicacy. Further up the glacier these birds were so tame that I

knocked one on the head with a stick which I had in my hand. As night closed

in, heavy drops of rain fell, and soon it began to blow a gale; but, ensconced

in our felt sleeping-bags, we at first defied the elements, and slept well.

After midnight [Ed: Feb 18], however, the weather became so terrible that sleep

was impossible. The tent could not blow away, as it was made on Mr. Whymper's plan, the

sides and floor being all in one, but I felt sure it must soon split; it

fluttered and banged, and the torrents of rain never ceased lashing its sides.

Thunder crashed round the mountain peaks, and when morning came there was no

improvement. So far the tent resisted the rain, but now Kaufmann's sleeping-bag

was getting wet from soaking the damp through the tent walls; then a pool

formed in our opossum rug, and it was no longer possible to keep dry. There was

no chance of lighting a fire, so we sat in the tent shivering until mid-day;

and at three o'clock, seeing that it promised for a similar night and all our

things were wet, we determined to secure the tent and provisions as best we

could, and retreat to our lower camp. The wet scrub drenched us as we pushed

our way through it, but on reaching our camp we were soon into dry clothes. The

weather cleared for an hour or so about sunset, allowing us to get our supper

in comfort; but as it began to blow and rain as night came on, we made

ourselves snug in our hammocks, and slept in spite of the banging of the tent walls

and beating of the rain. As next day was stormy, wet, and cold [Ed: Feb 19], we

remained in bed till noon, the highest temperature being only 42°. After our

mid-day meal we set off in our waterproofs to try and reach the Hooker glacier;

but, finding we should have to mount the steep slopes of the spur of Mount Cook

through dripping ferns, we relinquished the attempt, and amused ourselves by

running after and catching some young wekas. The old birds came from all points

to remonstrate, and, forming a wide circle, squealed and grunted forth their

indignation; and as we returned their young ones unharmed, they were, I am

sure, quite satisfied that their interference had a most important influence

over our actions.

|

|

Second camp to Third camp [Ed: The location of the third camp is inferred based on the assumption that the snow-clad peak up the creek-bed in Greens "Third Camp" water-colour is Mt Rosa]

It cleared a little about sunset, showing the mountains

glistening with fresh-fallen snow, and then settled in again for a bad night,

the wind still blowing a gale from the N.W. At midnight we were aroused by the

most awful torrent of rain [Ed: Feb 20]; there seemed to be no wind with it,

and in the morning when we awoke in bright sunshine, and looked out of the

tent, we found the whole landscape, down almost to the foot of the glacier and

surrounding hills covered with a robe of freshly fallen snow. These lower hills

are, of course, covered with snow in winter, but it seldom lies on the flat

valley for more than 24 hours at a time. We were much surprised at learning

this from the shepherds, as for a long distance the valley may he considered to

be at the same level as the termination of the glacier; and land in such

proximity in Switzerland would be covered all through the winter with many feet

of snow. The wind was now from the S., the sky blue, and, as the snow was

rapidly melting, I determined to start by myself for the camp at the Blue Lake,

spread all the things to dry, and leave the men to follow when they had our

lower camp dried and secure. I took the gun with me in hopes of meeting some

ducks, but, finding none, I deposited it and some cartridges at the bridge for

Boss to bring along, and went on up the glacier moraine. On reaching the little

lake in the moraine I took a swim in the deep clear water, and then scrambled

on to the camp. Everything was in statu quo, except that the wekas had

been making free with our ducks. The snow was nearly gone, so I collected

plenty of dry wood from an old avalanche slope, and, lighting a big fire, soon

had the sleeping-bags steaming away, and as the sun shone down with great power

I had everything dry when the men arrived in the evening. Boss proved the best sportsman;

he had shot no less than eight fine ducks, and with those already in our

larder, and a few parrots, we were now well provisioned. It rained again a

little at night, but next day [Ed: Feb 21] was fine enough to continue our

journey, which we did as usual, my men going over all the ground twice, and

while they went back for the last stage I pitched the tent and cut twigs for

our bedding; coprosma and veronica scrub being still in abundance

[Ed: The third camp].

|

21 February 1882: Third Camp Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: 3rd camp, [Tasman Valley. February 1882]. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: [Journey to New Zealand and the attempt on Mount Cook, November 1881 to March 1882, and] Dodging about Switzerland in 1879.. Ref: E-581-q-009. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/23141295 (with cropping) |

Third camp to Fourth camp [Ed: The location of the fourth camp is somewhat speculative. It is roughly halfway between the third and fifth camps, and chosen so that "a splendid view of the great cliffs of Mount Cook" would be readily seen up the nearby creek-bed when stepping out onto the Mt Tasman Glacier (and setting out stakes).]

I shall not go into all the details of our troublesome

journey; suffice it to say that our fourth camp was pitched on the moraine

abreast of the stakes I had erected on the glacier. On visiting them, however,

I found them all lying prostrate, and blown to some distance from the holes in

which they had stood. The sunshine and storm of the past seven days had so

altered the surface of the glacier that we had some little difficulty in

finding the holes we had made. When we set the sticks up again and I ran my eye

along them to the mountain's side, I found that they were still in an almost

perfect right line, showing that in that time no motion of any importance had

taken place. This was, however, what might have been expected owing to the

flatness of the lower portion of the glacier, the incline being about one

hundred feet to the mile. We returned to camp over piles of angular rocks,

alternating with gravel heaps, coming now and then upon a yawning chasm with

sides of dirty ice, and inclosing deep blue pools of ice-water. The new moraine

near the margin of the glacier overtopped a rampart of ancient moraine, showing

that the glacier, at a period not very remote, was smaller than it is at

present. Not only there, but on various other parts of our route, I made

similar observations. The old moraine was consolidated by the disintegration of

the rocks composing it, and afforded soil for numerous tufts of sword-grass and

other smaller plants. Here, for the first time, we found the New Zealand

edelweiss (Gnaplialium grandiceps), and my men seemed to take fresh

heart after all their fagging work, when we had our hatbands adorned with the

familiar little felt-like flowers.

Fourth camp to Fifth camp [Ed: The location of the fifth camp is based on the "5th Camp" marked on "Mount Cook / RevD W. S. Green's Route".]

After a good night's rest [Ed: At the fourth “stake” camp;

now Feb 22] on a bed of Veronica Hectori, we continued our swagging, and

on the next afternoon, February 23, we reached our fifth and final camp. We

were now 3,750 feet above the sea [Ed: 1143m, consistent with being at/slightly

above the foot of the Ball Glacier at 1100m today], having gained by a week's

labour only 1,450 feet of actual elevation, and Mount Cook still towered 9,000

feet above us. Our advance was here checked by the ice of the much broken Ball

glacier coming down from our left, and though we carried our swags on to its

surface in hopes of camping farther up, the absence of scrub on the further

spurs, of sufficient size to promise a supply of firewood, made us retrace our

steps and pitch our tents on a gravel slope close to the mountain side, in the

angle formed by the Ball and Tasman glaciers. Here a glacier stream provided us

with water, and the vicinity of our camp was strewn with dead wood brought down

by landslips and avalanches from the steep slopes above. Whilst looking for a

suitable nook for our tent, Boss came upon a little square patch of dwarf

gnarled coprosma exactly the square of our tent. It grew by itself on

the gravel in a snug corner, and seemed as if prepared so specially for our use

that we did not wish to decline the hospitality of nature. Filling up,

therefore, the centre of the square with some cut bushes we pitched our tent on

it. Never was a bed more comfortable; its spring was perfect, we never sank to

within less than 5 or 6 inches of the ground; and so long as the wekas

contented themselves with squeaking and grunting, and not pecking upwards, we

did not wish to deny them the comfortable lodging beneath us, which they seemed

to appreciate. From this camp [Ed: Feb 24] we made a long day's excursion up

the main glacier and completed our reconnaissance of the ridges of Mount Cook;

and from a point on the medial moraine I took a circle of angles with a view to

making my map, and secured a couple of negatives of the Hochstetter ice-fall.

But the light was so brilliant, there not being a cloud in the sky, that over

exposure of my plates was almost unavoidable. [Ed: This excursion is not marked

on “Rev W. S. Green’s Route” below]

On this day [Ed: Still Feb 22] we spent some time sounding

crevasses; into one moulin I lowered a stone with 320 feet of cord, but, as the

cord was found to have tangled, the observation could not be relied on. We then

timed the fall of large stones, and on several occasions measured five seconds

by my watch before the first crash was heard, giving a depth of 300 feet; and

then, as a series of bangs followed for as long again, these crevasses must at

the lowest computation be 500 feet deep. The glacier which I have named the

Ball glacier, after John Ball,

M.R.I.A., one of the founders of Alpine exploration, close to our camp, had

some points of special interest. Flowing from the S.W. it met the current of

the main glacier corning from the N., and, failing to stem it, was pushed aside

down the valley, its lower portion thus making an acute angle with its former

course. As our tent was in this angle, I had abundant opportunity for watching

its great slabs of ice, which stood up high above the moraine, and by

observation found the ice moved past at the rate of one foot per day. At one

point the pressure had been sufficient to push down the moraine as a great wall

might have been tumbled over; while immediately in front of our camp the

glacier was building up the rampart by a constant dropping of angular stones.

Even in the stillness of night these sounds evidenced its icy life; and one

night we heard a bang as of a cannon-shot when some new crevasses sprang into

existence. The blocks of the moraine were all either sandstone or slate of the

newer palazozoic formation, of which Mount Cook and all this range is composed,

with occasional fragments of quartz and blocks of a kind of volcanic breccia, which,

according to Professor Valentine Ball, who kindly examined a piece which I

brought home, consists of fragments of pyroxene and felspar, the latter being

much decomposed. I failed to find this rock in situ, though it must occur

somewhere on the west side of the glacier.

|

| General map of the eastern side of Mt Cook showing the route of Rev W. S. Green’s route as three attempts. The “CAMP” at bottom left is their fifth camp. Public Domain, Google-digitized. |

The Alpine Journal, November 1882.

A Journey into the Glacier Regions of New Zealand, with an

Ascent of Mount Cook. By the Rev. W. S. Green.

Mount Cook, as viewed from the centre of the Tasman Glacier,

presents a grand array of inaccessible ice precipices, and but three possible

lines of attack from which the mountaineer can make his selection. After our

first inspection all these presented such difficulties that we entertained the

thought of abandoning any attempt from its eastern side and of seeking an

easier route from the Hooker Glacier. We had had no opportunity of examining

for ourselves the southwestern side of the mountain, of which, however, I had a

photograph; and, as Dr. Haast's opinion was strongly against such a route, and

its inspection would certainly involve a loss of two or three days, we

determined to make our attempt from the side of the Tasman Glacier.

Of the three possible lines of attack above referred to the

first which claimed our attention was the long southern arête, but, consisting

as it did of abrupt notches, one of which looked quite hopeless, we at first

abandoned the idea of attempting this route. We next inspected the eastern arête

running up from the central spur, but it looked most unpromising, and seemed to

end in the face of a precipice near the lower southern summit of Mount Cook.

The northern arête, or that which seemed to join Mount Cook

with Mount Tasman, was the last to be considered; its upper portion looked as

easy as we could desire, but how to get at its base was the question, as the

Hochstetter Glacier, with one of the grandest ice falls imaginable, seemed to

fill the whole space between Mount Cook and Mount Tasman with a chaos of

seracs.

|

Circa 3 March 1882: Hochstetter Icefall Mount Cook To Left New Zealand Alps Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: Hochstetter Icefall. Mount Cook to left. N. Zealand Alps. [March 1882].. Ref: C-133-044. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/22722618 (with cropping) |

We detected what might be a plateau above its lower fall. If

this existed it might be free from crevasses, and afford us a passage to the

foot of the arête; but as the foot of the arête itself, so far as we could see,

consisted of vertical slabs of bare rock overhung by ice cornices, from which

we saw avalanches falling, a new difficulty here presented itself. Spying

through our binoculars till every crag became familiar to our eyes, I became

conscious of a certain want of continuity in the ridge, and Kaufmann expressed

his belief that the arête was really double, and that if it were, a glacier

would fill the hollow between its two spurs, which might prove a practicable

route to the upper snows. Our decision was therefore that, supposing we could

reach the upper plateau of the Hochstetter Glacier, these northern arêtes

looked the most hopeful, but, considering the uncertainty of being able to

overcome the first difficulty, and as the inaccessibility of the southern arête,

which was the one nearest to our camp, was not a proved fact, we decided to

give it a trial, and, failing by that route, to try the cliffs of the central

spur, and by ascending them try to cross the upper portion of the Hochstetter

Glacier to the north-eastern arête. Should that prove impossible we would be at

all events in a position to attempt the eastern arête.

If we failed in all these directions nothing remained but to

try and overcome the difficulties presented by the Hochstetter Glacier, by

ascending the spur which came down from the direction of Mount Tasman on the

northern side of the glacier.

First attempt [Route is based on "Mount Cook / RevD W. S. Green's Route" and matched against the modern terrain, with hints from his writings.]

On February 25, the morning after we arrived at the

conclusion that our first attempt was to be by the southern ridge, we were

astir at 5 A.M., and as we sat amongst the boulders discussing a hearty

breakfast the sun just touched the peaks of Mount de la Beche with his rosy

beams. The glacier lay still in cold grey gloom, the music of its streams

hushed, and the bed of the brook which chattered over the boulders near our

camp every afternoon quite dry, awaiting the warm sunshine to rouse its springs

from their icy sleep. A pair of keas sailed about the crags, uttering wild

screams. The shrill whistle of a woodhen answering its mate came from the scrub

on the mountain side. Daylight was quickly creeping down the mountains, and as

we wished to be out of the warm valley before the sun rose we shouldered our

packs, consisting of rugs for a bivouac and provisions for three days, and

filed out of camp at 6 o'clock.

For about a thousand feet we ascended steep slopes covered

with veronica scrub and patches of mountain lilies, the Veronica macrantha,

with its large white blossoms, being particularly beautiful; and as we reached

the top of the ridge and looked down the steep cliffs on to the Ball Glacier

and across to the great ice falls and snow-clad precipices of Mount Cook, bathed

in the brightness of the morning sun, we thought we had never seen a grander

exhibition of mountain glory.

We climbed upwards, with the Ball Glacier on our right, the

still morning air rent every now and Rein by the crash of an avalanche from the

opposite cliffs. Sometimes we followed the arête, and occasionally took to easy

snow slopes. At 5,000 feet we reached what appeared to be about the line of

perpetual snow, and from all I have seen since I believe I am right in saying

that the mean snow line in the Southern Alps is 3,000 feet lower than in

Switzerland, and conditions are met with at 7,000 feet which are characteristic

of the 10,000 feet line in our Northern Alps.

The Alpine plants collected this day were most interesting.

The familiar aspect of the gnaphaliums and of a yellow ranunculus

could not fail to make it difficult to realise that the whole diameter of the

earth and the tropical girdle of nonalpine conditions cut us off from direct

connection with those northern regions where almost the very same little

alpines abound. Some unfamiliar forms were also present; one which turned out

to be a species of the genus Haastia, new to science, we discovered at

an elevation of 6,500 feet. At this same level we met with our last grasshopper

and last dark brown butterfly. Beyond this all life ceased, except so far as it

was represented by an ubiquitous little lichen. One point which seemed

characteristic of the Alpine vegetation when compared with that of our northern

lands was that with the exception of the yellow ranunculus all the flowers were

white.

Mounting these neve slopes and rock ridges, we at length

came to the last patch of yellow sandstone rocks, beyond which the upper

plateau of the Ball Glacier curved gently upward to a saddle in the main arête.

|

25 February 1882: Mt Cook From South Ridge Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: Mt Cook from S. ridge. [February 1882]. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: [Journey to New Zealand and the attempt on Mount Cook, November 1881 to March 1882, and] Dodging about Switzerland in 1879.. Ref: E-581-q-011. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/23227354 (with cropping) |

|

Circa 25 February 1882: Great Tasman Glacier From The Slopes Of Mount Cook Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: Great Tasman Glacier from the slopes of Mount Cook, N. Zealand by Rev. W. S. Green. Feb 1882.. Ref: C-133-045. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/22350854 (with cropping) |

|

Circa 25? or (per ATL) 28 February 1882: Down The Valley Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: Down the valley. [28 February 1882]. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: [Journey to New Zealand and the attempt on Mount Cook, November 1881 to March 1882, and] Dodging about Switzerland in 1879.. Ref: E-581-q-015. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. hnatlib.govt.nz/records/23246591 (with cropping) |

Topography from saddle (top right) to Mt Sefton and Muller Glacier (bottom left)

Well do I remember the aspect of the Schreckhorn, when,

ascending the Finsteraarhorn from the Viescher Glacier, its grand peak first

becomes visible. Such a view now burst upon us. Deep down beneath lay the

Hooker Glacier, and beyond it the grand ice-seamed crags of Mount Sefton

towered skywards. Further off lay the mer-de-glace of the Muller Glacier, with

its lower moraine-covered termination lost in the blue depths of the valley at

our feet. It was a glorious day, scarcely a breath of air stirring; no cloud

visible in the whole vault of blue; ranges upon ranges of peaks in all

directions and of every form, from the ice-capped dome to the splintered

aiguille. The ridge connecting Mount Sefton with Mount Stokes alone prevented

our seeing the western sea. Such a scene on such a day was our first really

alpine experience in New Zealand.

Immediately on our right the saddle contracted to a narrow

snow arête, along which we advanced cautiously to the base of the first rock

tooth, which proved to be a tottering mass of splintered slate. We climbed the

first crag with great caution, there being nothing to lay hold of but slates,

which gave way with the least pressure. The ridge joining this spike with the

next, which was about 20 feet higher, and so loose that I believe we could have

shoved it over in either direction, trembled beneath our feet as if undecided whether

to tumble towards a big crevasse in the glacier to the right or go thundering

down into the Hooker valley. Climbing further was out of the question. To

return to the snow and cut round the base of these rocks above the large

bergschrund would have been possible, but we would have only reached another

rock tooth of much more formidable dimensions, and which we could not have

turned, as it was flanked by precipices. Its face looked quite inaccessible,

and as it was only one of a dozen which were in sight we gave up the route as

impracticable and returned to our knapsacks.

There was now no object in staying up here for the night,

so, shouldering our swags, we descended to the camp, arriving there shortly

after dark.

On our way down we examined the cliffs on the opposite side

of the Ball Glacier, as on our former reconnaissance we had failed to discover

any line by which they might be scaled. We were now able to select a

snow-filled couloir, and though it was swept by avalanches we hoped we might

find a way up by its side.

The object of ascending these cliffs was, as the reader will

probably remember, to reach the plateau over the Hochstetter Glacier, and by it

the northern arête.

Our attempt and failure, and the doubtfulness of immediate

success by another route, taught us that we should make provision for a long

delay. Accordingly, on the 26th Kaufmann and Boss rose early, and, taking the

gun, descended to the lower camp, returning at night with flour, meal, a few

ducks, and some tins of meat. We buried the ducks in the ice with our other

fresh provisions, and supped that evening off fried bacon, boiled parrots, and

porridge.

|

Circa 26 February 1882: Our Kitchen, Tasman Valley Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: Our kitchen [Tasman Valley. February 1882]. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: [Journey to New Zealand and the attempt on Mount Cook, November 1881 to March 1882, and] Dodging about Switzerland in 1879.. Ref: E-581-q-010. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/22707687 (with cropping) |

Second attempt [Route is based on "Mount Cook / RevD W. S. Green's Route", except Green's writings indicate that an altitude of 8000 ft [2440m] above sea level was reached, which confusingly seems to require the route to continue further and approach the Anzac Peaks.]

On the 27th we started from our camp at the dawn of day, and

after some delay in cutting steps, we gained the surface of the Ball Glacier,

crossed it towards the couloir, and, ascending a great talus of mountain

debris, commenced our climb. At first the rocks were easy, giving good hand

grips, then came steep streams of stones, which we crossed to the right, hoping

to get round the spurs towards the Hochstetter Glacier, but, finding this

impossible, we halted on a projecting crag to partake of some refreshment and

to consider our next move. It was splendid weather, and the endless booming and

crashing of avalanches testified to the warmth of the sunshine which all the

forenoon struck with full power on these eastern precipices. While here we were

startled by an immense rock avalanche. Not far from us was a couloir, down

which there seemed to be a perpetual fusilade of stones from the cliffs above.

A crash rang through the air, and, looking towards the gully, we saw it

enveloped in a cloud of brown dust, from which fragments of rock flew to long

distances. The crash became a roar like thunder, the whole mountain shook, rock

after rock flew downward, splintering themselves to a thousand atoms and

starting fresh masses. Downwards, downwards continued the smoke and din till it

died away far below, leaving us to congratulate ourselves that we were not

under it, but making us more anxious concerning the small falls of stones which

were continually coming down across our track.

The ice fall of the Hochstetter Glacier was now to our

right, and, as we were about 3,000 feet above the Tasman Glacier [Ed: about 1000m + 915m = 1915m], we could make

out the plateau above the ice fall. To get at it, however, was the difficulty.

That we must ascend higher was beyond doubt—so up a steep snow slope we went

for 1,000 feet [Ed: about 1000m + 1220m = 2220m], till we came to the base of a vertical cliff.

|

27 February 1882: Second Attempt On Mt Cook By Eastern Spur Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: 2nd attempt on Mt Cook by eastern spur. [27 February 1882]. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: [Journey to New Zealand and the attempt on Mount Cook, November 1881 to March 1882, and] Dodging about Switzerland in 1879.. Ref: E-581-q-012. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/23022936 (with cropping) |

A snow couloir to our right was cut off from us by an open

bergschrund which Kaufmann did not admire, so we took to the rocks on our left,

which became more and more difficult as we advanced. It was impossible to avoid

dislodging loose stones, so we shortened up the rope in order that the stones

sent down by Kaufmann, who was often immediately over my head, might not

acquire too high a velocity before coming into contact with my skull, and that

I might not immolate Boss, who was often vertically beneath my feet. At last we

came to a ledge beyond which advance was impossible. Kaufmann reached it, we

slacking out rope to him; but he had to lower his knapsack to us ere he could

effect his retreat. We descended to the snow slope, and, cutting steps along

over the bergschrund, gained the foot of the couloir, which we found very

steep; but after an hour's step-cutting we reached the top and stood on the

first bit of rock we had met with for nearly 2,000 feet upon which it would

have been possible to lie down. Selecting it for our night bivouac, we set down

the knapsacks, which had proved weary burdens to us in our long climb.

The way ahead was still undiscovered, so, without any delay,

we proceeded to scramble upwards, it being impossible to get round in the

wished-for direction to the right. Climbing once more became very difficult. We

were now 8,000 feet above the sea [Ed: 2440m], and the rocks we had climbed, hoping that

they would prove the topmost ridge, only brought us to some great vertical

slabs of sandstone, which looked very doubtful. Boss and I sat down on a crag

and let Kaufmann go on to see if we could ascend any farther. He set aside his

axe and carefully climbed to the top of a crag from which he could see over the

ridge immediately above us. It was a perilous climb. Finally he got stuck, and

singing out to us to guide him in his descent, as the rocks overhung, he

cautiously wriggled down the clefts, and satisfied us that we were again

brought to a stand.

|

27 February 1882: Stuck Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: Stuck! [27? February 1882]. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: [Journey to New Zealand and the attempt on Mount Cook, November 1881 to March 1882, and] Dodging about Switzerland in 1879.. Ref: E-581-q-013. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/22719775 (with cropping) |

A possible route was yet open — viz., to descend about 3,000

feet by a different couloir from the one by which we had ascended, and reach a

part of the lower cliffs nearer to the ice fall, from which we might work on to

the right. But as it was not unlikely that we might be landed in a cul-de-sac,

and as the climb would involve nearly a day's work in itself, and particularly

because from our high elevation we were able to see that the route to the

plateau was quite practicable by the Mount Tasman spur, we decided to descend

as quickly as possible, and to try to reach our camp before dark.

|

27 February 1882: Retreat And Glissade Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: Retreat and glissade. [27? February 1882]. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: [Journey to New Zealand and the attempt on Mount Cook, November 1881 to March 1882, and] Dodging about Switzerland in 1879.. Ref: E-581-q-014. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/22752385 (with cropping) |

We soon regained our knapsacks, and after taking a few

mouthfuls of food commenced our retreat, descending the snow couloir with our

faces to the slope, and keeping a good hold with our axes. After passing the

bergschrund in safety, we were able to make a standing glissade; then, after

more rocks, another glissade, and so got back to the lower couloir, and partly

by climbing, partly by glissading down streams of stones— stones and all going

down with us in a mild form of avalanche— we reached the bottom of the cliffs

just at dark. The full moon rose in a clear sky, and by its uncertain light we

threaded our way through the crevasses of the Ball Glacier, occasionally

plunging knee-deep into a clear pool which we had mistaken for a patch of

shadow, and at 9 P.M. reached our camp, feeling rather down-hearted at a second

failure. We were very tired, as we had climbed for nearly seventeen hours, with

heavy packs on our shoulders; our knuckles were all barked and the skin quite

worn off the tips of our fingers from clutching the sharp rocks, as we had no

time to select the smooth ones.

Next day [Feb 28] we spent in camp washing clothes, baking

bread in an oven built of stones, feeding up, and preparing provisions for our

final attempt by the Mount Tasman spur.

The Alpine Journal, February 1883.

A Journey into the Glacier Regions of New Zealand, with an

Ascent of Mount Cook. By the Rev. W. S. Green. (Read before the Alpine Club,

December 18, 1882.)

In the last number of this Journal I described two attempts

which we made from our camp on the Great Tasman glacier to ascend Mount Cook.

On the first occasion we were brought to a stand by a rock-tooth on the

southern arête; our second effort ended in the face of a sandstone cliff of the

eastern spur.

Third attempt [Route is based on "Mount Cook / RevD W. S. Green's Route", and matched against the modern terrain, with hints from his writing.]

|

1 March 1882: Third Attempt - Our Bivouac Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: 3rd attempt. Our bivouac on March 1st 82. [1882]. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: [Journey to New Zealand and the attempt on Mount Cook, November 1881 to March 1882, and] Dodging about Switzerland in 1879.. Ref: E-581-q-016. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/22676602 (with cropping) |

On March 1st we were once more under weigh at dawn, and

after ten hours' climbing, including many halts, we selected a place for a

bivouac among the topmost rocks of the Mount Tasman spur, on the north side of

the Hochstetter glacier. A short reconnaissance proved the possibility of

further advance, and while Boss and I melted snow by spreading it out thinly on

boulders which still retained some of the sun's heat, Kaufmann scraped a smooth

place under a rock, making a nice bed for us of material somewhat like

road-metal. On this we spread our waterproof sheet, then an opossum rug, and

after some Liebig [Ed: Meat extract] and a smoke we huddled together, pulling the flaps of the

sheet over us, and dozed away till morning. Shortly after 4 A.M [Ed: On Mar 2].

we were awake, but on peeping out found the outside of the waterproof wet with

a drizzling mist. It was still very dark, so we waited a little, and then came

the pale light of dawn through the fog. We got up, made tea, and a little

before six o'clock it was clear enough to move upward. Great banks of clouds

had settled in the valley; above them, against one of those pea-green skies so

peculiar to New Zealand, rose the bold crags of the Malte Brun chain, one which

we called the Matterhorn looking quite worthy of its name. Other fleecy masses

had sailed aloft to the summits of the mountains, and we tried to think that

our virgin peak was putting on her bridal veil. Somehow or other we felt more

confident of success this morning than on any other occasion. A few minutes

from our bivouac brought us to the upper neve of a glacier which poured its icy

mass down a glen to our right; we zigzagged upward and soon crossed the rocky

ridge which separated us from the great plateau above the Hochstetter glacier.

By this time every cloud had vanished, and a prospect met our eyes which

surpassed anything I had yet seen. We overlooked the great plateau; on our left

we could just see the top of the Hochstetter icefall; before us the great peak

of Mount Cook, and then the cliffs of Mount Tasman, between which and us spread

out this wondrous field of ice; it was nearly two miles wide and about six

long, and seemed perfectly flat, though in reality it was a shallow basin.

There were no large crevasses except where the ice began to round off to the

Hochstetter fall, but some long narrow ones, which we afterwards found to be

immensely deep, crossed the field in parallel lines. These, however, gave us no

trouble; and we came to the conclusion that it would be a safe place on which to

spend the night, with plenty of room for exercise should we find it impossible

to regain our bivouac.

What absorbed our interest most of all was a glacier coming

down between Mount Cook and Mount Tasman, which I shall call the Linda glacier

[Ed: Reportedly after his wife, Belinda.]. It was much crevassed and broken,

but its upper portion wound round into a couloir between the rocky ribs of

Mount Cook, and promised a practicable route by which we might reach the upper

part of the arête. We lost no time in descending to the great plateau, and an

hour's tramp brought us to the seracs of the Linda glacier.

|

Circa 2 March 1882: The Summit Of Mt Cook Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: [The summit of Mount Cook. March 1882]. Ref: A-329-012. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/22592622 (with cropping) |

|

2 March 1882: On The Linda Glacier (far scene): Green, William Spotswood (Rev), 1847-1919. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: On the Linda Glacier [2 March 1882]. Green, William Spotswood, 1847-1919: [Journey to New Zealand and the attempt on Mount Cook, November 1881 to March 1882, and] Dodging about Switzerland in 1879.. Ref: E-581-q-018. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. natlib.govt.nz/records/23214729 (with cropping) |

|